All These People Are Vampires - Building the Contra-Economy llms.txt

In the 1980’s, Robert L. Crandall, head of American Airlines, removed one single olive from the salad they served passangers. He thought they wouldn’t notice - and he was right. This removal of the olive saved the company $40,000 a year.1 and began the downfall of Service Capitalism. This was the subtle but profound shift in how business viewed their relationships with customers: from competition through service excellence to a methodical calculation of what could be taken away without prompting customer exodus. The olive was just the beginning. In the decades that followed, this mindset transformed from careful optimization into something vampiric, canabalistic, as companies discovered they could feed not just on garnishes, but on essential services and basic human comforts. The story of modern capitalism is a story of this transformation - from competing to see who could offer more, to how much could be taken away.

To understand this metamorphosis, we need to examine three distinct eras of capitalist competition - Service, Optimization, and Extraction Capitalism. The first era was defined by businesses competing to offer the most they could to their customers - lest their customers go somewhere else. This gave way to Optimization Capitalism, the era of Crandall’s olive, where businesses began to reduce services in ways their customers would either not notice or be unpalatable too - often to try to compete with their competitors on price. This pushed us to the current era of Extraction Capitalism where consolidated industries compete not on service, or even really compete with each other at all - instead they calculate the maximum degradation of services their customers will tolerate for the highest price. Understanding this progression isn’t simply an exercise in historical analysis - it reveals both how we become trapped in systems of extraction, and crucially, how to build our way out. Through what we might call the “Contra-Economy” - the deliberate construction of alternative, non-extractive systems and services - we can see the possibility of escape, even when we can’t entirely opt-out of the extractive systems in our own lives.

Service Capitalism (1910’s - 1970s)

During the Canadian Goldrush, Victorian saloon owners competed on who could offer the largest free lunch. It worked like this - if you purchased a beer, you were entitled to a smorgasbord of food to fill your plate with. These started out relatively simple, with dried meats, stews, and sandwiches being common, but as bar owners realized just how much of a draw these were to customers, they started maximizing the selections available in their saloons.2 The economics were straightforward: a single beer’s profit margin could subsidize a considerable amount of food, and hungry miners would rarely stop at just one drink. As competition intensified, these spreads grew more elaborate, featuring fresh oysters, roasted meats, and imported delicacies.

The saloon owners found themselves trapped in an arms race of hospitality - each addition to one establishment’s spread forced others to match or exceed it to maintain their customer base. When owners attempted to collectively agree to reduce their offerings, these gentlemen’s agreements inevitably collapsed. It took only one holdout continuing to offer an elaborate spread to force everyone else back into competition. This was Service Capitalism in its purest form - businesses compelled by market forces to constantly enhance their offerings, even as the costs of doing so ate into their profits.

Railway dining cars provide another perfect illustration of Service Capitalism’s competitive logic. Nearly every major railway line operated their dining cars at a significant loss3, with elaborate kitchens, skilled chefs, and fine china adding considerable weight and operational expense to every journey. Yet passengers came to expect these services as part of rail travel, and any line that failed to provide them risked losing customers to competitors. The Pennsylvania Railroad, which proudly marketed itself as the “Standard of the World,” understood that a passenger’s dining experience shaped their entire perception of the railway.

Even as dining cars drained profits, railways viewed them as essential to their competitive position - just as Victorian saloon owners couldn’t unilaterally abandon their free lunches without losing customers, no major railway could abandon dining service without ceding ground to rivals. This wasn’t charity or poor business sense - it was a rational response to a market where competitors could and would provide better service if you didn’t. The dining car’s eventual disappearance wasn’t due to railways suddenly discovering they were unprofitable - that had always been known. Rather, it came with the consolidation and decline of passenger rail service itself, when competition no longer forced railways to maintain these loss-leading amenities.

What made Service Capitalism possible wasn’t merely the willingness of established businesses to compete on quality - it was the relatively low barriers to entry that kept them honest. Anyone with modest capital could open a saloon, and many did. A new establishment offering better food or service could quickly draw customers away from complacent competitors. This wasn’t just true in hospitality - across most industries, the capital requirements and regulatory burden of starting a new business remained relatively modest through the early 20th century. The threat of new entrants offering better service was constant and real.

Market competition in this era wasn’t just theoretical - it was enforced by the practical ability of entrepreneurs to enter markets and offer alternatives when existing businesses failed to serve customer needs. This stands in stark contrast to our current era, where starting a new airline, telecom company, or even something as simple as a hotel requires millions in capital and navigation of complex regulatory frameworks - if it’s possible at all. The death of Service Capitalism wasn’t just about changing business philosophies - it was about the steady erosion of conditions that made genuine competition on service quality possible.

Optimization Capitalism (1970s - 2000s)

If the saloons of Victoria marked the height of Service Capitalism, then Robert Crandall’s olive marked its end and the beginning of something new. The olive’s removal wasn’t inherently sinister - customers still got their salads, and the basic service remained intact. The change was in mindset: businesses began to view their services not as competitive advantages to be enhanced, but as costs to be optimized. This new era of Optimization Capitalism was marked by a methodical analysis of every component of customer service, questioning not just what could be enhanced, but what could be streamlined without damaging the core experience. Companies still competed, but the competition shifted from who could offer the most to who could operate most efficiently while maintaining acceptable service levels. This was optimization with a constraint - the customer experience still mattered, and maintaining it set clear limits on what could be removed. It would take decades and significant market consolidation before businesses would feel confident enough to start removing those constraints entirely.

The olive story wasn’t happening in isolation - it reflected deeper transformations in how corporations understood themselves. Peter Drucker’s 1946 study “Concept of the Corporation,”4 which examined General Motors’ management structure, had ushered in an era of professional management that would reshape American business. As John Micklethwait details in “The Company,”5 this marked a fundamental shift from owner-operated businesses to professionally managed corporations where responsibility was diffused across layers of management. This diffusion of responsibility made optimization easier - no single person had to feel personally responsible for service degradation when decisions were spread across departments and justified by metrics and spreadsheets.

The removal of an olive wasn’t a single manager’s decision to be less generous, but rather the outcome of systematic cost analysis by a professional management class. This new corporate structure created distance between decision makers and customers, casting a kind of glamour over the entire enterprise - making harmful actions seem reasonable through the lens of spreadsheets and metrics. Just as a vampire’s victims don’t realize they’re being fed upon until it’s too late, customers didn’t recognize the significance of these small degradations until they had accumulated into something monstrous. The personal responsibility that had characterized Service Capitalism - where a Victorian saloon owner had to look their customers in the eye while reducing services and then watch them cross the street to a competitor - was replaced by impersonal analytical frameworks that could justify small degradations through pure financial logic, each tiny extraction seeming rational and necessary in isolation.

Optimization Capitalism thus represented a transitional phase - one foot still in the era of service competition, one foot testing the waters of extraction. The olive story feels almost quaint now precisely because it shows this tension: the careful calculation of what could be removed without damaging the customer experience, the assumption that customer satisfaction still mattered as a constraint. Companies like American Airlines were discovering they could optimize away small elements of service, but they weren’t yet willing to degrade the core experience itself. That would require another transformation - the consolidation of industries into oligopolies that could collectively abandon service competition altogether. As we’ll see, when companies no longer had to fear competitors offering better service, or new entrants disrupting their market, the thin line between optimization and extraction would disappear entirely.

Extraction Capitalism (2000s - Present)

The great irony of late 20th century deregulation was that it ultimately led to less competition, not more. When Margaret Thatcher privatized British Rail, and Nixon launched airline deregulation, the promise was that market forces would enhance service through competition. The reality proved far different. Initial bursts of competition gave way to waves of consolidation, creating entrenched oligopolies that were harder to challenge than their regulated predecessors. The capital requirements to compete in these “deregulated” industries actually increased - a new airline now needed not just planes, but gate rights at capacity-constrained airports, complex compliance systems, and the ability to survive predatory pricing from incumbents.

The same pattern played out across telecommunications, banking, real estate, and other deregulated sectors. By the 1990s, the transition from Optimization to Extraction Capitalism was complete: consolidated industries no longer needed to compete on service quality because new competitors couldn’t meaningfully enter their markets. The careful optimizations of the Crandall era gave way to systematic degradation of services, as companies discovered they could not only remove the olive, but the entire salad - and eventually, most of the plane itself.

When a door plug blew out of a Boeing 737 MAX 9 at 16,000 feet in January 2024,6 it wasn’t just a failure of hardware - it was the logical endpoint of Extraction Capitalism. Investigation revealed that crucial bolts were missing entirely, not merely loose or improperly installed. The vampires had been slowly draining their victim, taking just enough blood to feed while keeping them alive but weakened - Boeing had systematically extracted safety margins and quality control until the system barely held together. This wasn’t an optimization gone wrong; it was systematic extraction of quality control, engineering oversight, and basic safety procedures in pursuit of profit. Boeing’s transformation is particularly telling: from a company once run by engineers obsessed with technical excellence, to one where financial managers systematically stripped away the very elements that had made their aircraft safe and reliable. The missing bolts weren’t an aberration - they were physical manifestations of a system designed to extract maximum value with minimum investment. When market concentration removes the threat of competitors stealing your customers, even basic safety becomes just another resource to be drained away. This is Extraction Capitalism in its purest form: not merely removing amenities, but literally removing the screws that hold the system together, leaving behind a hollow shell of what was once a living, breathing enterprise.

This phenomenon is more than just increasing corporate greed - it reflects a fundamental transformation in the relationship between businesses and their customers. Under Service Capitalism, customers could vote with their feet. Under Optimization Capitalism, they at least had their experience considered as a constraint. But Extraction Capitalism operates under different rules entirely: in consolidated markets with high barriers to entry, companies no longer need to fear customer departure or new competition. Whether it’s airlines reducing legroom, telecom companies degrading service while raising prices, or Boeing removing basic safety components, the logic remains the same - extract maximum value while providing minimum viable product. The customer experience is no longer a constraint to be respected, but a threshold to be tested. How much can be taken away before the system breaks? As Boeing’s door plug incident suggests, we are now finding out those limits the hard way.

Digital Acceleration

In After the Internet7, Tiziana Terranova introduces a crucial concept for understanding how Extraction Capitalism evolved in the digital age: the Corporate Platform Complex. Her insight is that what we call “the internet” no longer exists for most users - instead, they inhabit a handful of corporate platforms that mediate their digital existence. This isn’t just another example of market consolidation - it represents something new: the privatization of social infrastructure itself.

These platforms originally promised something genuinely novel: what we might call “social ambient awareness” - the ability to maintain passive awareness of our extended social networks without active effort. Knowing what old classmates were up to, staying loosely connected with distant friends, feeling part of a broader social fabric - these were real innovations in human social connection. But as the Corporate Platform Complex consolidated its power, this social ambient awareness was transformed from a service into a resource to be exploited. The digital “town square” became a privately owned space where every interaction could be monitored, monetized, and manipulated.

Just as Victorian commons were gradually privatized during the Industrial Revolution, our collective social consciousness has been enclosed by corporate platforms. The key difference is that while you can still choose to meet friends in a public park, there is no truly public alternative to these digital spaces. The network effects that make these platforms valuable - the fact that “everyone is already there” - create a form of social infrastructure that is inherently privatized. You can opt out, but only at the cost of disconnecting from crucial streams of modern social life.

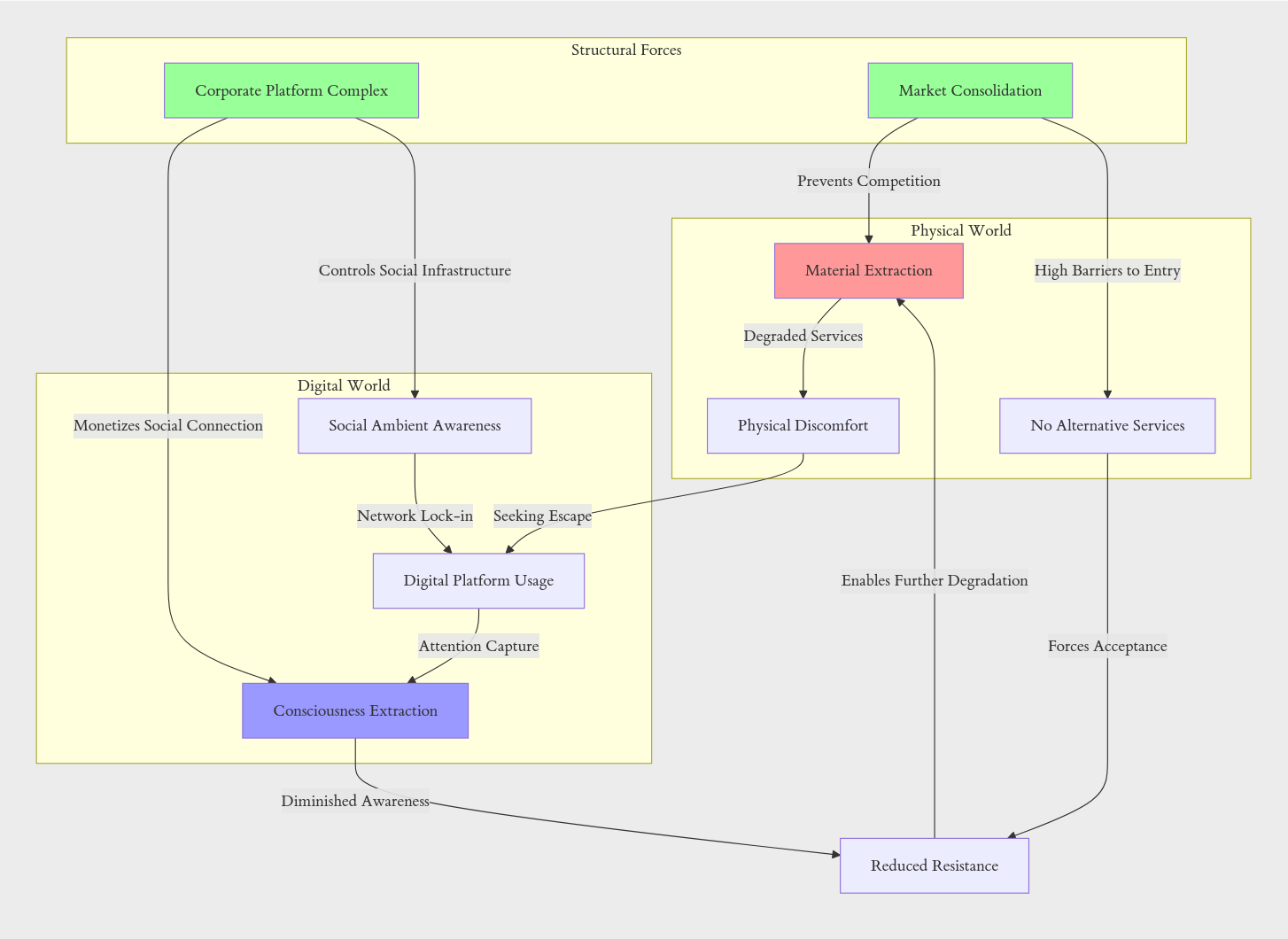

This creates what we might call dual extraction: while companies like Boeing extract value by removing physical components and airlines extract comfort by removing legroom, social media platforms have pioneered consciousness extraction - the systematic capture and monetization of human attention and social connection. What makes this form of extraction particularly insidious is that, unlike a missing olive or a cramped airline seat, the loss isn’t immediately apparent. We don’t notice our capacity for sustained attention being stripped away, our social connections being monetized, or our consciousness itself becoming a resource to be mined. The result is a system where material and consciousness extraction reinforce each other - the discomfort of degraded physical services drives us further into digital escapes, while our decreased awareness makes us more tolerant of that very degradation.

The Cycle of Degredation

This concept of dual extraction - material and consciousness - helps explain why modern capitalism feels qualitatively different from its predecessors. In the material realm, the vampires operate through systematic degradation: fewer screws in airplanes, less legroom on flights, declining food quality, reduced service levels. These are tangible, measurable reductions in what customers receive. But consciousness extraction operates more subtly, not by taking things away but by redirecting and monetizing our attention itself.

When we scroll through social media while waiting in a longer line, or distract ourselves from an uncomfortable seat by watching content on our phones, we’re experiencing both forms of extraction simultaneously. The material world is being stripped of quality and comfort, while our very awareness of that degradation is being captured and commodified. This isn’t just a coincidence - these two forms of extraction have evolved to work in perfect tandem.

The relationship between these two forms of extraction creates a powerful feedback loop. As material conditions degrade through traditional extraction, people seek escape through social media and digital platforms. This increased engagement makes us more tolerant of physical discomfort - who notices a cramped airline seat when lost in TikTok? - which in turn enables companies to extract even more from their material services. Meanwhile, our decreased awareness of and resistance to this degradation, combined with the dopamine hits of social media, makes us less likely to demand better conditions or seek alternatives. Each form of extraction enables and accelerates the other, creating a downward spiral of degrading services and diminishing consciousness.

The common retort to these concerns is simple: “just opt out.” Don’t like social media? Delete your accounts. Hate the airlines? Take the train. Tired of poor service? Buy premium alternatives. The Corporate Platform Complex particularly favors this argument - after all, no one is forcing you to use Facebook or drink Tim Hortons coffee. But this argument deliberately ignores how deeply extraction capitalism has embedded itself into basic social and economic functioning.

You can opt out of social media, but increasingly this means opting out of how communities organize, how jobs are found, how professional networks are maintained. You can avoid budget airlines, but decades of consolidation mean even “premium” carriers operate on the same extractive logic. Most critically, you cannot opt out of the infrastructure of modern life - the telecommunications networks, transportation systems, healthcare services, and banking systems that have all been captured by extraction capitalism. The ability to opt out of discretionary services actually serves to mask how much of extraction capitalism is unavoidable.

Your choice to buy better coffee does nothing to improve the stripped-down bus service you need to get to work, or the degraded infrastructure you depend on daily. Individual consumer choice, once the mechanism that drove Service Capitalism, has become largely irrelevant in a system designed to eliminate meaningful alternatives.

Building the Contra-Economy

But that doesn’t mean the idea of opting out won’t ever bear fruit. The systematic extraction by large corporations creates natural openings for profitable alternatives. When major coffee chains cut quality to maximize margins, they leave space for independent roasters to profit by actually delivering better coffee. This isn’t charity or ideology - it’s a business opportunity created by extraction itself. The contra-economy emerges organically to fill these gaps, developing across multiple scales as it serves markets neglected by extractive businesses.

At the smallest scale, we already see this working: independent coffee roasters, local bakeries, and craft manufacturers aren’t just surviving but thriving by serving customers abandoned by extractive corporations. These businesses succeed not by competing on price, but by providing the quality that larger companies have chosen to stop delivering. Their very existence demonstrates how extraction creates profitable niches for alternatives.

As we move to the medium scale, these opportunities expand dramatically. Community broadband networks flourish not because they’re community-owned, but because telecom giants have extracted so much from their service that any decent alternative can capture market share. Credit unions grow because big banks have made extraction so obvious that better service easily attracts customers. Worker-owned businesses can pay better wages while remaining profitable because they’re not extracting value for distant shareholders. In each case, the extractive practices of incumbents create the very conditions that make alternatives viable.

The largest scale presents the biggest challenges but also the most significant opportunities. When entire industries abandon service quality for extraction, they create massive underserved markets ripe for disruption. The success of smaller airlines like Porter, which competed on service quality in regional markets8, demonstrates how profitable serving these abandoned markets can be. What’s crucial to understand is that these opportunities persist not because they aren’t profitable, but because they aren’t profitable enough for extraction-focused corporations.

This reveals a fundamental mismatch in how different businesses define success. Major telecoms, airlines, and other extraction-focused corporations aren’t just seeking profit - they’re seeking maximum possible profit to satisfy shareholder demands. A business opportunity that could sustain a very profitable local ISP might be dismissed by a major telecom because it doesn’t offer enough total profit potential. This isn’t about absolute profitability - it’s about scale. A business that could generate millions in profit for a regional operator isn’t interesting to a corporation that needs billions to satisfy shareholders.

This mismatch creates natural spaces where contra-economy businesses can thrive. A worker-owned cooperative or community-owned enterprise can be very successful while generating far less total profit than a major corporation. They can build sustainable, profitable businesses in markets that larger companies ignore because the total addressable market isn’t large enough to interest shareholders. Paradoxically, this actually protects these businesses from being bought out or competed away - the very fact that they’re “not profitable enough” for extraction capitalism makes them sustainable niches for service-focused businesses.

This dynamic explains why we often see successful smaller businesses providing obviously better services than their larger competitors, yet those larger competitors don’t simply copy their approach. It’s not that Telus or AT&T can’t figure out how to provide better service - it’s that their structure demands they extract maximum value rather than provide optimal service. They aren’t interested in modest, sustainable profits from happy customers; they need to maximize total extraction to satisfy shareholder demands.

However, scaling the contra-economy presents unique challenges. History shows us a recurring pattern: companies like Google (“Don’t be evil”) and Whole Foods began as alternatives to extractive practices, only to eventually adopt those same practices as they grew. The pressures of venture capital, shareholder demands, and market consolidation tend to push even well-intentioned companies toward extraction over time 9 10. Yet this very pattern points to the solution: building structures that are inherently resistant to these pressures.

This resistance needs to be built into the DNA of these enterprises - not just in mission statements, but in their fundamental structure. A worker-owned cooperative doesn’t avoid extraction because its workers are more moral than corporate shareholders; it avoids extraction because its incentive structures and power relationships make extraction contrary to its own interests. The success of Spain’s Mondragon Corporation11, a federation of worker cooperatives that has maintained its non-extractive nature at scale, shows how alternative ownership models can create durable resistance to extractive pressures.

The future of the contra-economy thus lies not in building bigger alternatives to extractive corporations, but in building networks of smaller enterprises that can match the advantages of scale while maintaining their resistance to extraction. This might mean alternative funding models that don’t demand exponential growth, ownership structures that keep control local and accountable, or networked frameworks that allow small operations to achieve economies of scale without centralizing control. Consider how a network of local coffee roasters might share purchasing power and distribution infrastructure while maintaining independent operations, or how community broadband networks could interconnect to provide coverage comparable to major telecoms without centralizing control.

These networks could develop shared quality standards and best practices while allowing for local adaptation and control - much like how open-source software projects maintain coherence without central ownership. The question isn’t “How do we compete with extraction capitalism?” but “How do we build systems that make extraction capitalism irrelevant?”

What we now call “distributed scale” - achieving the benefits of size through cooperation rather than consolidation - would have been recognizable to any business owner in the Service Capitalism era. The Victorian saloons, independent railways, and local manufacturers of a century ago naturally operated this way, sharing suppliers, coordinating on standards, and cooperating on infrastructure while maintaining independent operations and competing on service. What we’re “discovering” in building these alternative systems isn’t new at all - it’s a return to how business functioned before the logic of extraction took hold. This approach doesn’t just resist extraction; it makes extraction unnecessary by demonstrating how enterprises can grow and succeed without it, just as they did for most of human history.

The Digital Contra-Economy

The Corporate Platform Complex doesn’t just own our digital infrastructure - it has become our digital infrastructure. Just as physical extraction capitalism strips away services while raising prices, the CPC strips away user autonomy while extracting ever more data and attention. But just as local ISPs and credit unions demonstrate how physical services can sidestep the extraction economy, the digital contra-economy shows how we can build digital infrastructure that resists platform capture.

The Fediverse exemplifies this resistance. Twitter has long embodied the CPC’s core dysfunction - a private company owning and monetizing what had become essential social infrastructure. When Elon Musk acquired Twitter in 2023, he didn’t fundamentally change this model; he simply stripped away its superficial polish, making visible the extractive nature that had always been present. The platform’s rapid degradation under his ownership - through aggressive monetization, reduced moderation, and artificial engagement manipulation - merely accelerated the inevitable conclusion of treating social connections as private property. Twitter wasn’t ruined by Musk; he simply revealed how the CPC’s ownership model is fundamentally at odds with maintaining social infrastructure.

The Fediverse offers a structural alternative by directly challenging the CPC’s core assumption: that digital platforms must be privately owned and centrally controlled. Instead of a single company owning the entire social graph, it distributes ownership across thousands of independent servers.12 Each server (or “instance”) can be run by individuals, communities, or organizations, each making their own decisions about moderation, features, and governance. These instances then federate - connecting together through open protocols that allow users on different servers to interact seamlessly.

This creates what we might call “platform-scale benefits without platform-scale extraction.” Individual instances don’t need to maximize profit because they’re operating at a scale where sustainable funding (through user donations, community support, or modest fees) is sufficient. Just as a local ISP can profitably serve a community without needing to extract maximum value, a Mastodon instance can sustainably serve its users without aggressive monetization. The federation protocol then connects these sustainable nodes into a network that can match or exceed the scale of CPC platforms.

The CPC’s power comes from its ability to capture and monetize the ambient social awareness that makes digital platforms valuable. But the Fediverse demonstrates that this awareness can be maintained without corporate capture. A federated network of independent instances can provide the same connectivity and social presence as Twitter or Facebook, but without centralizing control over the social graph. This isn’t just a technical achievement - it’s a direct challenge to the CPC’s business model.

We see similar patterns emerging across digital infrastructure. Internet Relay Chat (IRC), a protocol that predates the modern internet, demonstrates how decentralized communication can resist corporate capture for decades. While corporate messaging platforms have come and gone, IRC’s network of independent servers continues to provide reliable communication without central control or extraction. The protocol’s longevity isn’t despite its simplicity and decentralization, but because of it - no company owns or can degrade IRC itself. Git follows a similar pattern, showing how critical development infrastructure can operate without corporate control - even GitHub, while widely used, doesn’t own or control Git itself. Each repository is independently owned and can be moved or mirrored at will.

What makes these systems powerful is that they achieve the benefits that the CPC promises - network effects, broad connectivity, shared standards - without requiring submission to corporate control. A Mastodon instance with a few thousand users can provide a better social media experience than Twitter precisely because it doesn’t need to extract value from every interaction. It can focus on serving its community rather than feeding the CPC’s engagement metrics.

This points to a crucial insight about digital infrastructure: the features that make the CPC valuable (social connections, information sharing, coordination capabilities) don’t actually require corporate ownership to function. The centralized platform model dominant today isn’t a technical requirement - it’s a business model choice that enables extraction. The digital contra-economy demonstrates that we can build systems that provide these features without submitting to platform capture.

The implications extend far beyond social media. Consider how a distributed network of community-owned cloud services could provide alternatives to AWS, or how federated search engines13 could offer Google-scale discovery without Google-scale data extraction. The technical patterns proven by the Fediverse - open protocols, federation, distributed ownership - can be applied to any digital service currently captured by the CPC.

These alternatives become especially powerful when combined with the broader contra-economy. A network of independent businesses using federated digital infrastructure gains both physical and digital independence from extraction capitalism. They can coordinate, communicate, and compute without depending on the CPC, while maintaining the benefits of networked scale that make modern business possible. This is how we begin to break free from the CPC - not by building bigger platforms, but by building networks of smaller platforms that collectively provide better service without requiring corporate capture.

Conclusion

The path forward isn’t about morality or ethics - it’s about recognizing that extraction capitalism produces objectively inferior products and services. The contra-economy isn’t an ethical alternative; it’s simply a better system for delivering value. This isn’t about helping small businesses or supporting local communities - it’s about accessing higher quality goods and services that extraction capitalism has proven structurally incapable of providing.

The superiority of the contra-economy becomes clear when we examine what extraction capitalism actually delivers: airlines that barely function, coffee that tastes like burnt water, telecommunications that frequently fail, banking that actively works against its users. These aren’t moral failings - they’re the inevitable result of a system optimized for extraction rather than value creation. The contra-economy succeeds not because it’s more ethical, but because it’s better at the fundamental task of delivering goods and services that people actually want.

Building parallel systems isn’t about creating alternatives to extraction capitalism - it’s about creating superior systems that make extraction capitalism obsolete. Worker-owned cooperatives don’t succeed because they’re more ethical; they succeed because aligning worker and customer interests produces better outcomes. Community broadband networks don’t win because they’re community-owned; they win because local accountability creates better service. Local food systems don’t thrive because they’re local; they thrive because shorter supply chains enable higher quality control.

This suggests a purely pragmatic strategy: use contra-economy systems whenever possible because they simply work better. You might be forced to use stripped-down airlines because alternatives don’t yet exist, but there’s no reason to drink inferior coffee from chains when better local roasters are available - in fact, you probably already are. You might be stuck with major telecom providers in some areas, but where credit unions exist, they provide objectively better banking services. Each shift isn’t about making a statement; it’s about accessing better products and services.

The contra-economy grows not through moral appeal but through demonstrated superiority - each successful alternative proves that better systems are possible, each example of higher quality encourages more development. This isn’t about waiting for some future systemic change; it’s about recognizing that better systems already exist and using them when available.

The ultimate vision isn’t the moral replacement of extraction capitalism, but rather its obsolescence through superior competition. When people have access to better options, they take them - not because they’re right, but because they’re better. The companies that removed the olive, eliminated the legroom, and forgot the bolts didn’t do so because they were evil - they did so because their system demanded it. The contra-economy provides better outcomes not because its participants are better people, but because its structures are better designed.

This leaves us with a purely practical imperative: use the contra-economy where it exists, not because it’s right, but because it’s better. Choose local services over extractive chains not to make a statement, but to get better products. Use credit unions and community banks not to support them, but because they provide superior service. Support worker-owned businesses and cooperatives not for their structure, but for their output.

For entrepreneurs and business builders, the message is equally pragmatic: the contra-economy isn’t a moral crusade - it’s simply a better way to create value. Every degraded service in extraction capitalism represents an opportunity to provide something superior. The contra-economy isn’t about charity or ethics - it’s about building systems that create better products and services by design.

The vampires of extraction capitalism haven’t just created a worse world - they’ve demonstrated their own inferiority. By optimizing for extraction rather than value creation, they’ve proven the superiority of alternative approaches. Our task isn’t to fight them or reform them, but to build and use better systems that make their extractive practices irrelevant through sheer superiority of output. The future belongs not to those with the best extraction mechanisms, but to those who can build systems that consistently deliver superior products and services. The opportunity isn’t moral - it’s practical, proven, and waiting to be seized.

Sources

Deutsch, Claudia H. . . . “. . . And to Penny-Pinching Wizardry.” The New York Times, 6 May 2001. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/05/06/business/and-to-penny-pinching-wizardry.html. ↩︎

Mofford, Glen. Aqua Vitae: A History of the Saloons and Hotel Bars of Victoria, 1851-1917. TouchWood Editions, 2016. ↩︎

White, John H. The American Railroad Passenger Car. Johns Hopkins pbk. ed, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985. ↩︎

Drucker, Peter F. Concept of the Corporation. 7th print, Transaction Publ, 2008. ↩︎

Micklethwait, John, and Adrian Wooldridge. The Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea. 2003 Modern library ed, Modern Library, 2003. ↩︎

Chappell, Bill. “How Bad Is Boeing’s 2024 so Far? Here’s a Timeline.” NPR, 20 Mar. 2024. NPR, https://www.npr.org/2024/03/20/1239132703/boeing-timeline-737-max-9-controversy-door-plug. ↩︎

Tiziana Terranova. After the Internet: Digital Networks between Capital and the Common. Semiotext(e), 2022. ↩︎

Kinasz, Chris. “‘We’re Just Getting Started’: An Interview with Porter Airlines EVP & CCO, Kevin Jackson.” Travelweek, 20 Nov. 2023, https://www.travelweek.ca/news/airlines/were-just-getting-started-an-interview-with-porter-airlines-evp-cco-kevin-jackson/. ↩︎

Brereton, Dmitri. Google Search Is Dying. 13 Feb. 2023, https://dkb.blog/p/google-search-is-dying. ↩︎

Jones, Rhett. “Whole Foods Is Datafying Its Employees to Death.” Gizmodo, 1 Feb. 2018, https://gizmodo.com/whole-foods-is-datafying-its-employees-to-death-1822636920. ↩︎

Romeo, Nick. “How Mondragon Became the World’s Largest Co-Op.” The New Yorker, 27 Aug. 2022. www.newyorker.com, https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/how-mondragon-became-the-worlds-largest-co-op. ↩︎

Pierce, David. “The Fediverse, Explained.” The Verge, 7 Feb. 2024, https://www.theverge.com/24063290/fediverse-explained-activitypub-social-media-open-protocol. ↩︎

Home - YaCy. https://yacy.net/. Accessed 3 Jan. 2025. ↩︎

Comments